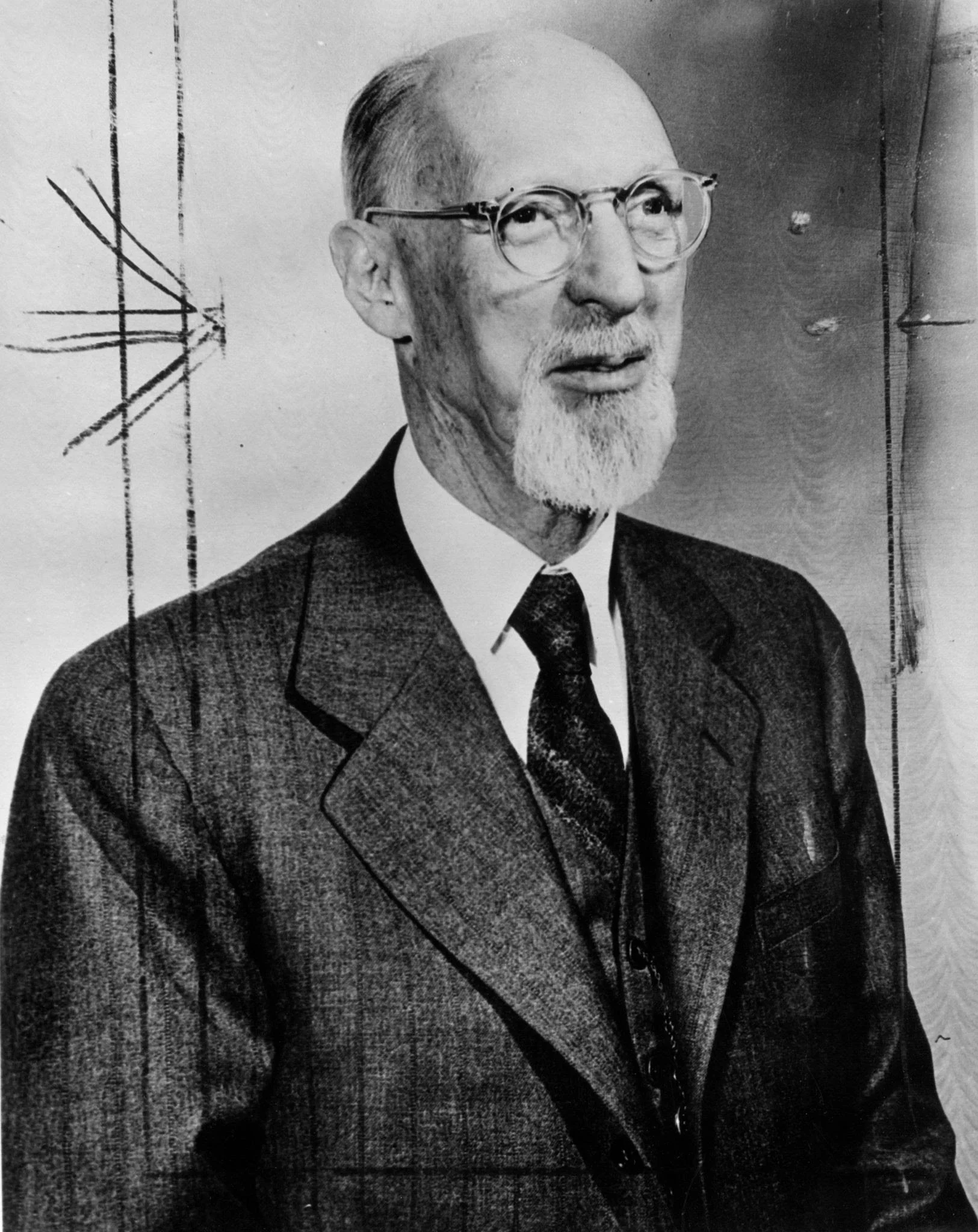

About Juanita

Juanita Brooks was a highly influential historian, author, and educator from Utah, known for her pioneering work in documenting the history of the American West, particularly Latter-day Saints (members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints) and the interactions between Mormon settlers and Indigenous peoples. Recognized as a trailblazer in the field of southern Utah history, she is admired for her courage in addressing difficult subjects within her own community. Her work remains a valuable resource for historians and readers interested in the history of the American West and the LDS Church.

Quick Facts

Born:

January 15, 1898

Bunkerville, Nevada

Death:

August 26, 1989

St. George, Utah

Schooling:

Bachelor of Arts degree from Brigham Young University, Master's degree at Columbia University

Honorary Degrees:

Utah State University, Southern Utah State College, University of Utah

Early Life

Juanita Leone Leavitt was born on January 15, 1898, to Henry Leavitt and Mary Hafen in Bunkerville, Nevada, and raised there. Her grandparents on both sides were polygamists; her paternal grandfather, Dudley Leavitt, being one of the primary founders of Bunkerville. From a young age she developed an interest in history when, "her brilliant, sensitive, and imaginative mind was saturated from childhood in Mormon lore."

She was often employed as a grade school teacher in nearby Southern Utah. In 1919 she married Ernest Pulsipher, who died of lymphoma a little more than a year later, leaving her with an infant son, Leonard Ernest Pulsipher. After his death, she resumed her job as a teacher, and then received her bachelor's degree from BYU. Her first published work was a poem titled "Sunrise from the Top of Mount Timp," which appeared in the LDS periodical Improvement Era in 1926.

Gallery

Academia and family life

After earning her bachelors degree, she settled in St. George, Utah, and became an instructor of English and Dean of Women from 1925–1933 at the LDS-backed Dixie Junior College. While on a sabbatical from Dixie College from 1928–1929, she obtained a master's degree from Columbia University.

In 1933, the state of Utah discontinued funding for parochial Mormon post-secondary education. She resigned from the college after the program was cut and, in the same year, married a widower named Will Brooks. She became stepmother to his four sons, Walter, Bob, Grant, and Clair, and they became true brothers to her son Ernie. Within five years the couple added a daughter, Willa Nita, and three more sons, Karl, Kay and Tony to their family. Juanita had affectionate relationships with all of her children, including her step-sons, describing her family as "compound-complex". She would sometimes complain that she lacked time to write because of her family, but she also stated that her loved ones were essential to her happiness. Her children spoke highly of their mother at her funeral, telling stories of her nurturing character.

Her calling as a historian and writer was frequently at odds with her position as a believing Mormon woman. As a woman, she was expected to, and indeed, desired to devote her life to homemaking and motherhood.

— Wikipedia

Tension with the Church

“I do not want to be excommunicated from my church for many reasons, but if that is the price that I must pay for intellectual honesty, I shall pay it—I hope without bitterness.”

Juanita Brooks, faced tension with The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) primarily due to her groundbreaking research on sensitive historical topics, most notably the Mountain Meadows Massacre. This tragic event occurred in 1857, when a group of Mormon settlers, along with Native American allies, attacked and killed around 120 emigrants traveling through southern Utah.

Brooks' work, particularly her 1950 book The Mountain Meadows Massacre, was one of the first to openly explore the role of local church leaders and settlers in the massacre, contradicting the church’s earlier narratives, which had downplayed or obscured the church's involvement. While Brooks did not directly blame Brigham Young, she emphasized the involvement of prominent local LDS leaders, sparking discomfort within the church.

Key reasons for the tension:

Legacy and Impact

Books by Juanita

Quotes from Juanita

FAQ

-

No, Juanita Brooks was not excommunicated from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church).

-

No. She maintained a strong commitment to her faith, balancing her dedication to historical accuracy with her personal beliefs.

-

Juanita Brooks was progressive for her time regarding issues of race, particularly within the context of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ (LDS) racial policies, including the restriction on Black members holding the priesthood, which lasted until 1978. While Brooks did not frequently write on the subject, she privately voiced her discomfort and disapproval of the church’s racial restrictions and felt that they contradicted the teachings of equality and justice that they espoused and she valued.

Brooks believed in fairness and was known for her compassion toward marginalized groups, evident in her treatment of Native American histories in her writing and her sensitive approach to difficult aspects of Mormon history. She quietly but firmly hoped for change within the LDS Church regarding racial policies, though she generally avoided public statements that might put her at odds with church leadership. Her stance reflected her overall approach: advocating for reform and historical accuracy while remaining within the church and respecting its authorities.

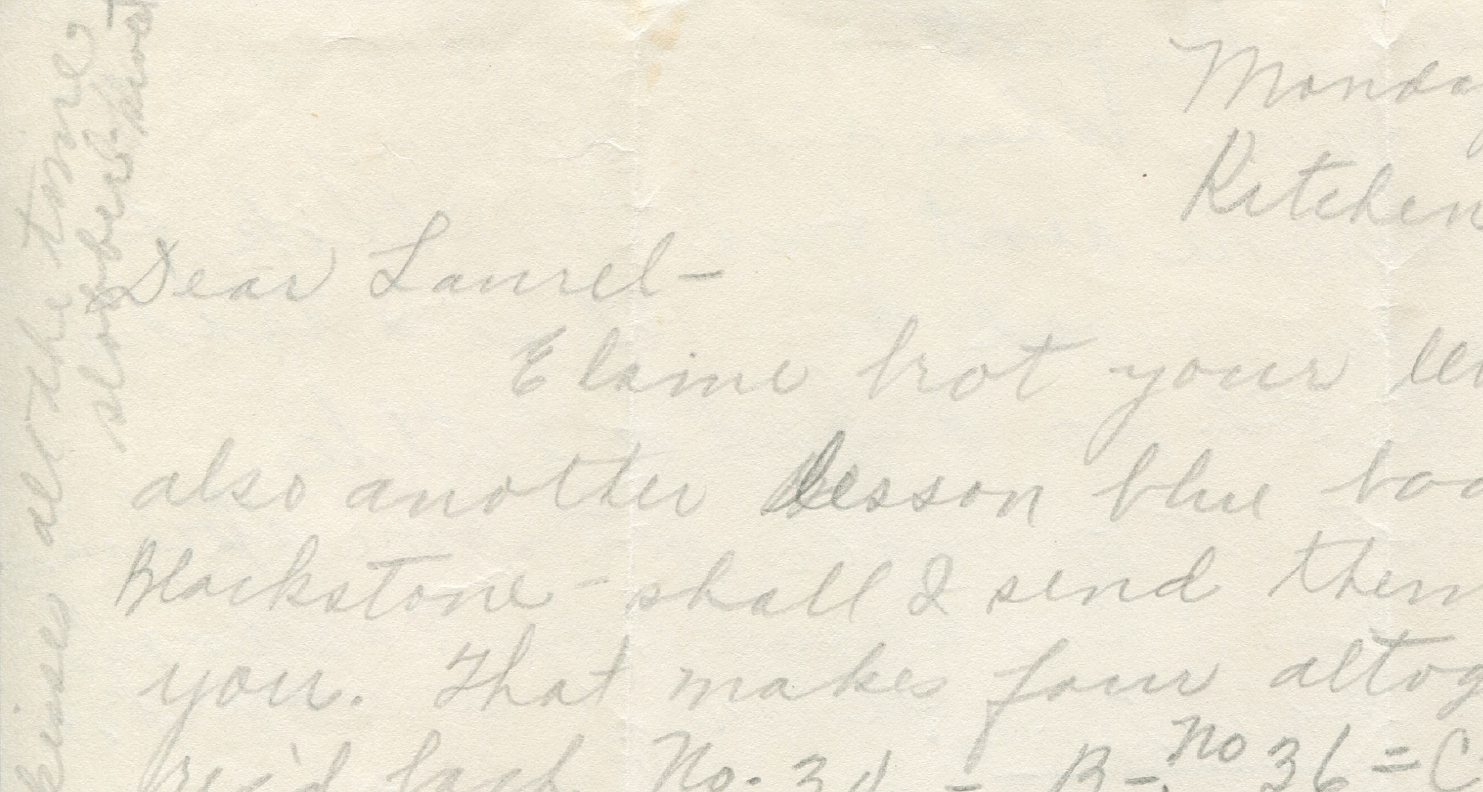

Brooks Home

Built by her father-in-law, George Brooks, the Brooks family lived in the house and Juanita wrote much of her work there. The house underwent several changes over the years, including the addition of two-story bedrooms in 1949, a new kitchen and living room in 1954, and the expansion of the root cellar into a full basement.